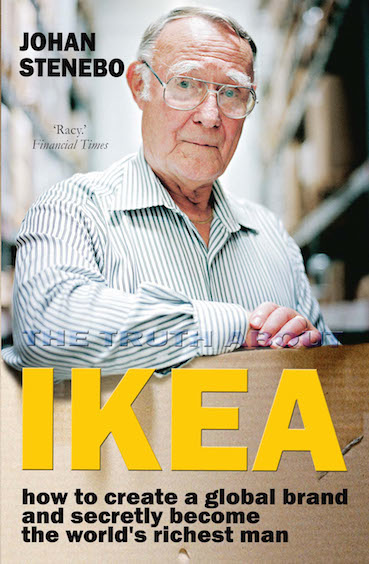

Recently deceased billionaire Ingvar Kamprad started IKEA in rural Sweden at the age of 17 and built it into a global behemoth. Here’s how. By Johan Stenebo

Upon the death of Ingvar Kamprad, the world’s richest man in secret, we ought to ask how did he create the IKEA success story? Here is a man of stark contrasts who, until his death on 28 January 2018 age 91, owned IKEA as sole proprietor, building a global furniture behemoth from a single general goods store in rural Sweden when he was a neo-Nazi sympathizer. I wrote a book about the different strands – some good, some ambiguous – of this business story. But there are two core strands of his success that one can easily isolate.

Upon the death of Ingvar Kamprad, the world’s richest man in secret, we ought to ask how did he create the IKEA success story? Here is a man of stark contrasts who, until his death on 28 January 2018 age 91, owned IKEA as sole proprietor, building a global furniture behemoth from a single general goods store in rural Sweden when he was a neo-Nazi sympathizer. I wrote a book about the different strands – some good, some ambiguous – of this business story. But there are two core strands of his success that one can easily isolate.

Simplicity is a virtue

First and foremost, there is the genius of Kamprad himself since he was the instigator of most things (albeit not everything) within IKEA. Ingvar’s key mantra that ‘simplicity is a virtue’ is still central to the success story of IKEA. Only mediocre people propose complicated solutions, he would repeat over and over again.

That simple yet fertile message, powered enormous expansion. During my two decades as one of the company’s executive team in various parts of the company, and several years as Ingvar’s right-hand man, IKEA’s turnover went from SEK 25bn to 250bn, from 30,000 to 150,000 employees, from around 70 stores mainly concentrated in Northern Europe to 250 with global coverage. It is still an unparalleled expansion and achievement. IKEA remains the biggest and longest-running success story of modern times in Sweden if not all over the world.

A slick machine

After this simple idea, as plain as an unopened flatpack, there is the IKEA-machinery, the global value chain from forest to customer, that Ingvar and his team have built and tuned to perfection. In order to understand IKEA one has to understand what the company really does. And understand how IKEA does it. Its enormous organisation cooperates around the clock throughout the year in order to produce what the IKEA customers want. Each and every one of the 11 business sections work in three-year cycles: the present year, the next and the one after that. In other words, they work with three parallel focuses. For the present year, the focus will mainly be on the supply of the existing range. Obviously especially on the catalogue range, since that is the only promise by IKEA to its customers around the world. At the same time a lot of time is dedicated to securing the launch of new products for the next new range and catalogue. Yet the plan and range for the following year must also always be present. Everything is connected, coordinated and efficient as clockwork. Ingvar would not allow disruptive fiefdoms to emerge and create grit in the machine.

In reality there are only three ways for a company, irrespective of its product, to compete with others in the same market. Either you make your products more cheaply than the competitors or you make them better (different in some respect) or you make them both more cheaply and better. IKEA decided to concentrate on the third strategy right from its inception.

This means that at IKEA price and volume are at the heart of its machinery as much as anything else. This is the very part of the machine that truly makes everything else happen and delivers the necessary growth for expansion. It is as simple as brilliant in its structure.

Start by asking for a considerable volume from a supplier and get the offered price down in exchange for a promise that the agreement will last a few years. Selling the volume won’t be a problem since lower cost prices mean lower retail prices. Next year the order is increased again, against the promise of a substantially lower price. And so the wheel goes round year in and year out. The momentum of the wheel is mainly decided by the negotiation skills of the buyers.

Try to imagine a stack of pine or spruce logs comprising almost 200,000,000 logs. That is how immense IKEA’s need for forest raw material is per year. IKEA has been far-sighted in its endeavour to secure its need for timber, not least thanks to Kamprad’s complete understanding of how things might look in the future. When the Berlin wall fell in 1989 and the map of Eastern Europe changed overnight, IKEA’s best buyers had already left the starting blocks.

IKEA now has what none of its competitors has – suppliers in around 70 countries in all parts of the world consisting of around 1,400 companies. Purchases are dealt with through a network of purchasing offices. Ongoing questions like product quality and constancy of orders are frequently checked. These companies are linked to IKEA through more or less long-term agreements which stipulate volume and cost price per unit. Normally it is precisely the large volumes that IKEA orders that gives the company a price advantage over its competitors, since the home furnishing market is fragmented in most markets and only global in the case of IKEA. Even big US companies like Target and Home Depot, which dwarf IKEA, are essentially national or regional.

While Kamprad was, by his own admission, far from perfect, IKEA itself continues to create more and jobs and economic stability for people around the globe. Now, thanks to Ingvar’s last stroke of foresight it is also a virtually tax-free inheritance of enormous, but undisclosed, size for his descendants.

Johan Stenebo is the author of The Truth About IKEA: How To Create A Global Brand And Secretly Become The World’s Richest Man (Gibson Square £9.99) bit.ly/thetruthaboutikea